There are many lessons to be learnt from the heavy electoral setback suffered by the Shiv Sena this month in Maharashtra, be it temporary or terminal. These lessons are not merely about an ethno-nationalist party’s decline. They are about how the Indian state, its dominant political formations and street-level coercive power have historically interacted.

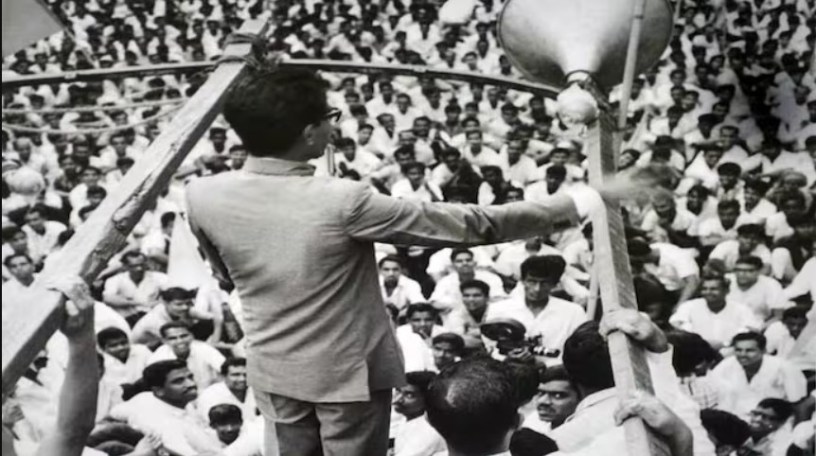

The following is a translation of my FB post originally penned in Malayalam drawing on a speech given by my father, CPM leader Pattiam Gopalan, in the Lok Sabha in May 1970. He made this speech shortly after the infamous bandh called by Shiv Sena in Bombay which targeted south Indians and their property and right to livelihood.

1. Historically, the rise of the Shiv Sena is a textbook case of elite patronage producing uncontrollable mass politics. The Sena was the Congress party’s Frankenstein’s monster. Its founder-leader Bal Thackeray was consciously cultivated to physically dismantle leftist trade unions in Bombay, which were seen as obstacles to capital accumulation and so-called labour discipline. What began as a tactical instrument soon hardened into a permanent structure of organised intimidation, a “quotation gang” with political legitimacy

2. In the late 1960s, the Congress achieved a great degree of success with this strategy. The “containment” of organised labour in Bombay served both political and economic interests (of their cronies). The lesson was not lost on other ideological actors. The RSS, observing the utility of such formations, sought to replicate the model in communist strongholds elsewhere. Thalassery in Kannur was chosen as one such laboratory. While disruption was achieved, full political capture remained elusive, a piece of history I have documented in my book Kannur.

3. As is often the case with instruments of coercive politics, the Shiv Sena outgrew its creators. Once unleashed, it surpassed the Congress party’s capacity to control it. Thackeray and his cadre innovated ideologically, shifting from class confrontation to identity mobilisation. South Indians were identified as the first internal “other”. Linguistic chauvinism and cultural resentment became the organising principles of expansion. The slogan Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi captured this transition from economic conflict to cultural exclusion

4. This logic of exclusion did not stop there. The target soon shifted from regional outsiders to Muslims. This evolution, chronicled in Marathi street theatre, marked a decisive ideological turn. Bal Thackeray’s politics now rested on a majoritarian imagination that framed minorities as demographic and cultural threats. In this sense, his rhetoric bears a striking resemblance to contemporary global right-wing movements, including MAGA-style anti-immigration politics in the United States and Europe

5. The Jana Sangh, and later the BJP, found in the Shiv Sena a natural ally. Thackeray offered something they lacked back then: a proven template for street mobilisation, intimidation and cultural polarisation. For leaders like Vajpayee and Advani, Thackeray was not merely a partner but a model, someone who demonstrated how ideological politics could be translated into raw power on the ground

6. By 2014, however, the ideological convergence had been subsumed by organisational arrogance. The BJP’s new leadership, intoxicated by electoral dominance and pursuing inorganic expansion, displayed little regard for “institutional memory”, much to the anguish of this regional, ethno-nationalist entity. The Shiv Sena was treated as dispensable. Advani’s advice to keep the Sena close in 2014 was reportedly dismissed

7. The eventual split in the Shiv Sena was not accidental. It was structurally induced. Once the BJP established supremacy in Maharashtra, the Sena was reduced to dependency within its own traditional base. A party built on dominance of the street found itself hollowed out by a larger, more centralised hegemon

8. Attempts these days to absolve the Congress of responsibility for this trajectory are intellectually dishonest. The use of caste, clique formation and controlled factionalism has long been embedded in the Congress’s political culture. Even in Gandhi’s era, representative committees often followed informal, upper-caste gatekeeping. Gandhiji’s remark about Kamaraj being a clique leader illustrates the continuity of elite control mechanisms cloaked in moral language.

9. The events of 3 March 1970 expose the depth of state complicity. That day Bombay was paralysed following Thackeray’s bandh, called after consultations with Congress leaders. In the Lok Sabha, CPI(M) leader Pattiam Gopalan’s speech on the episode (attached below) was devastating. He highlighted not only the surrender of state authority but also the political diminishment of Union Home Minister YB Chavan. The government had no credible response. Gopalan’s warning that Thackeray was attempting to establish “a Rhodesian-style” regime was not hyperbole, but an early diagnosis of authoritarian ethnic politics in the making